By: CropLife International

A staple food is one that is eaten regularly and in such amounts that it is a main part of a population’s diet, supplying a significant amount of energy and nutrition. These crops are in such high demand that they need to be high-yielding and resistant to pests, diseases and environmental stresses.

There are more than 50,000 edible plant species on the planet, but only a few hundred contribute meaningfully to our diet. In fact, just 15 crops provide 90 percent of global energy intake and “the big four” – maize, rice, wheat and potatoes – are staples for about 5 billion people. Such reliable, widespread crops are the basis of food systems and human subsistence. Plant science technologies, such as crop protection products and biotech seeds, have helped keep these staples stable, even in the face of climate change.

The most productive staple crop in the world is maize, which yielded 1.1 billion tons in 2019 alone, followed by wheat, rice and potatoes at 765, 755 and 370 million tons, respectively. But what about staple crops beyond these heavy hitters? Here is a look at the unsung heroes of agriculture. In different parts of the world, they help feed rural communities and entire countries, with more nutrients than the big four.

Soybeans have been grown as a crop for thousands of years. As legume plants, they fixate nitrogen, absorbing this essential nutrient from soil bacteria, which is a talent most crops lack. This means fertilizer is usually not needed when growing soybeans. Moreover, plant science technologies have led to higher and higher soybean yields. No wonder they are one of the world’s fastest expanding crops!

While low-carb soybeans are highly prized for their oil, they are considered a staple food because of their protein. They are among the best sources of plant-based protein in the world, plus contain vitamins and minerals. They are processed into milk, tofu, tempeh and other high-protein products. Japan and China are major consumers of these foods.

Global soybean production is concentrated in Brazil and the United States on sizeable farms, but the crop is also grown in many other countries by smallholder farmers.

In both developed and developing countries, the adoption of biotech soybean varieties has more than doubled yields since the 1960s. That’s why these varieties account for up to 81 percent of global production. Herbicide-resistant biotech soybeans also reduce greenhouse gas emissions by as much as 80 percent as they allow for no-till farming, which keeps carbon in the soil.

Cassava is a staple for more than 600 million people across Africa, Asia and Latin America. It is an excellent source of vitamin C and a good source of fiber and potassium. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations identified it as a vital crop in the fight against hunger and formed a partnership to bolster its genetic improvement.

Cassava is grown by many farmers in developing countries due to its ability to thrive in poor soils as it requires less water and fertilizer than alternatives and can be harvested anytime from eight to 24 months after planting, meaning it can be left in the ground as a living food store. The only caveat is that long periods in the soil makes cassava more susceptible to pests and diseases.

Cassava farmers have typically struggled with these challenges as the crop is notoriously resistant to traditional plant breeding techniques due to unreliable flowering patterns.

However, gene-edited cassava flowers more reliably, giving researchers great hope for the future of this crop. Biotech varieties could help control pests and diseases as well as enhance yields and nutrition. This crop has untapped potential; experts estimate that introducing such varieties could increase cassava production in Africa by 150 percent.

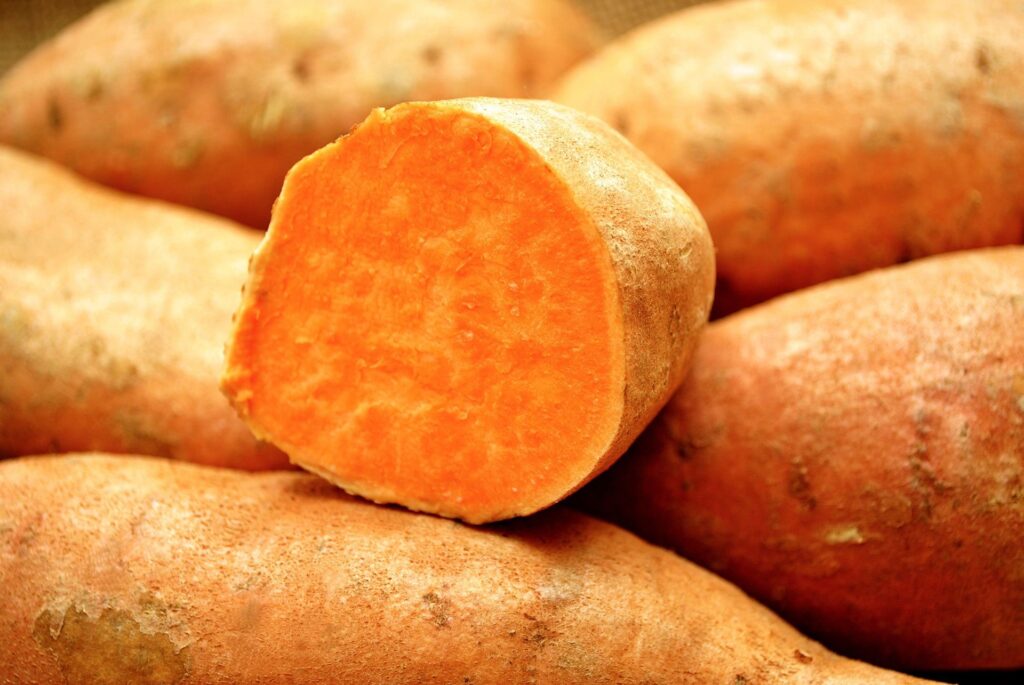

Sweet potatoes are vital in the diets of people in parts of Africa and Asia, where they are a major source of subsistence. They are a rich source of vitamin A and good source of fiber.

Drought-tolerant sweet potatoes grow incredibly well on marginal land and do not require a large degree of care. Farmers are sweet on these qualities so these potatoes have expanded faster than all other staple crops in sub-Saharan Africa in the last 20 years. They have also attracted the attention of researchers who would like to use sweet potatoes to improve the health of children.

In rural sub-Saharan Africa, around 48 percent of children have vitamin A deficiency. This can degrade immune systems, increasing the risk of diarrhea and even causing blindness. In 2009, this dire situation led to the formation of the Sweet Potato for Profit and Health Initiative, which developed varieties with greater virus resistance, drought tolerance and lower sugar levels. It led to commercial production of orange-fleshed sweet potato biofortified with beta carotene. This variety significantly raises vitamin A levels in children, further cementing the sweet potato’s status as a vital staple.

Known as an “orphan crop” due to not being widely traded, yams are a staple food for more than 100 million people in the tropics, particularly western and central Africa. They are “yam-packed” with vitamin C, potassium and fiber.

Contrary to popular belief, yams are distinct from sweet potatoes; they are less sweet, more starchy, larger and cylindrical with bark-like skin that’s difficult to peel and flesh that’s purple or pink when mature. Yams can grow up to 1.5 meters and 60 kilograms!

Indigenous to Africa and Asia, yams are now also commonly grown in the Caribbean and Latin America. There are more than 600 varieties!

Farmers favor them as they can be stored for four to six months without refrigeration, giving people a vital safety net between growing seasons.

The yam’s orphan status has led to a recent research push into biotech improvements. The genetics of yams are the least understood among major staple food crops, partly due to biological restraints. The domestication of wild yam species is ongoing in Africa, further widening the genetic base. As such, this crop has more potential for biotech innovation than any other major staple and efforts to improve the yam’s disease resistance and yield are underway.

High in protein and potassium, sorghum has been a staple crop in semi-arid areas of Asia and Africa for hundreds of years and millions of people rely upon it. This crop is well-liked by subsistence farmers due to its ability to thrive in harsh environments where other crops grow poorly or fail. It is the only viable grain and plant protein for many of the world’s most food-insecure people.

Most varieties are heat- and drought-tolerant, while higher-yielding dwarf varieties have seen increasing commercial production in countries like the United States.

Combining these varieties with modern crop protection and smart water management can see yields increase by as much as eight times.

Sorghum’s natural qualities make it ideally suited for drought-susceptible regions, with climate change expected to further enhance its status as one of the most important cereal crops on the planet. This led to it being selected for biofortification, as natural varieties contain a compound that reduces the body’s ability to use iron and zinc, which can cause anemia. These new varieties tackled this challenge while also gaining beta-carotene, which the body converts into vitamin A. This is a great example of plant science improving nutrition for some of the world’s most vulnerable people.

With populations and food systems across the world facing the impacts of climate change, combined with the ever-increasing need for farmers to produce more with less, safeguarding staple crops is more important than ever. While “the big four” of maize, rice, wheat and potatoes are caloric powerhouses, other staple crops offer more nutritionally like soybeans, cassava, sweet potatoes, yams and sorghum.

With populations and food systems across the world facing the impacts of climate change, combined with the ever-increasing need for farmers to produce more with less, safeguarding staple crops is more important than ever. While “the big four” of maize, rice, wheat and potatoes are caloric powerhouses, other staple crops offer more nutritionally like soybeans, cassava, sweet potatoes, yams and sorghum.